How a UC Santa Barbara physics lab’s collaboration with YouTube giant Kurzgesagt turned complex planetary defense research into a global phenomenon with nearly 8 million views.

When UC Santa Barbara physics professor Philip Lubin received an email from “Kurzgesagt” in July 2024, he had a simple question for his research group.

“I had never heard of them,” Lubin, who directs the NASA-funded planetary defense program at UCSB, admitted in an email to his department chair. “I asked the younger UCSB researchers in our group if they knew what Kurzgesagt was. Sadly, the answer I received was very much a generational issue and they basically responded, ‘What, you do not know who they are?’”

The early career researchers in his group — including assistant specialists Brin Bailey and Sasha Cohen — certainly knew. Kurzgesagt, German for “in a nutshell,” is one of the world’s most popular science communication channels, translating complex topics into dazzlingly animated videos for an audience of over 20 million subscribers.

That generational divide between a professor deep in research and the younger scientists who grew up on the platform turned out to be the perfect launching pad for one of the department’s most significant public outreach successes to date.

The Kurzgesagt team wanted to feature the Lubin group’s research on planetary defense. A year later, the collaboration resulted in a video titled, “Can Humanity Stop A Planet-Killing Asteroid?“

On its first day, it had over a million views. Within a week, three million.

Today, that “cute” video, as Lubin first called it, has been viewed over 7.9 million times across Kurzgesagt's English, German, Spanish, French and Portuguese channels.

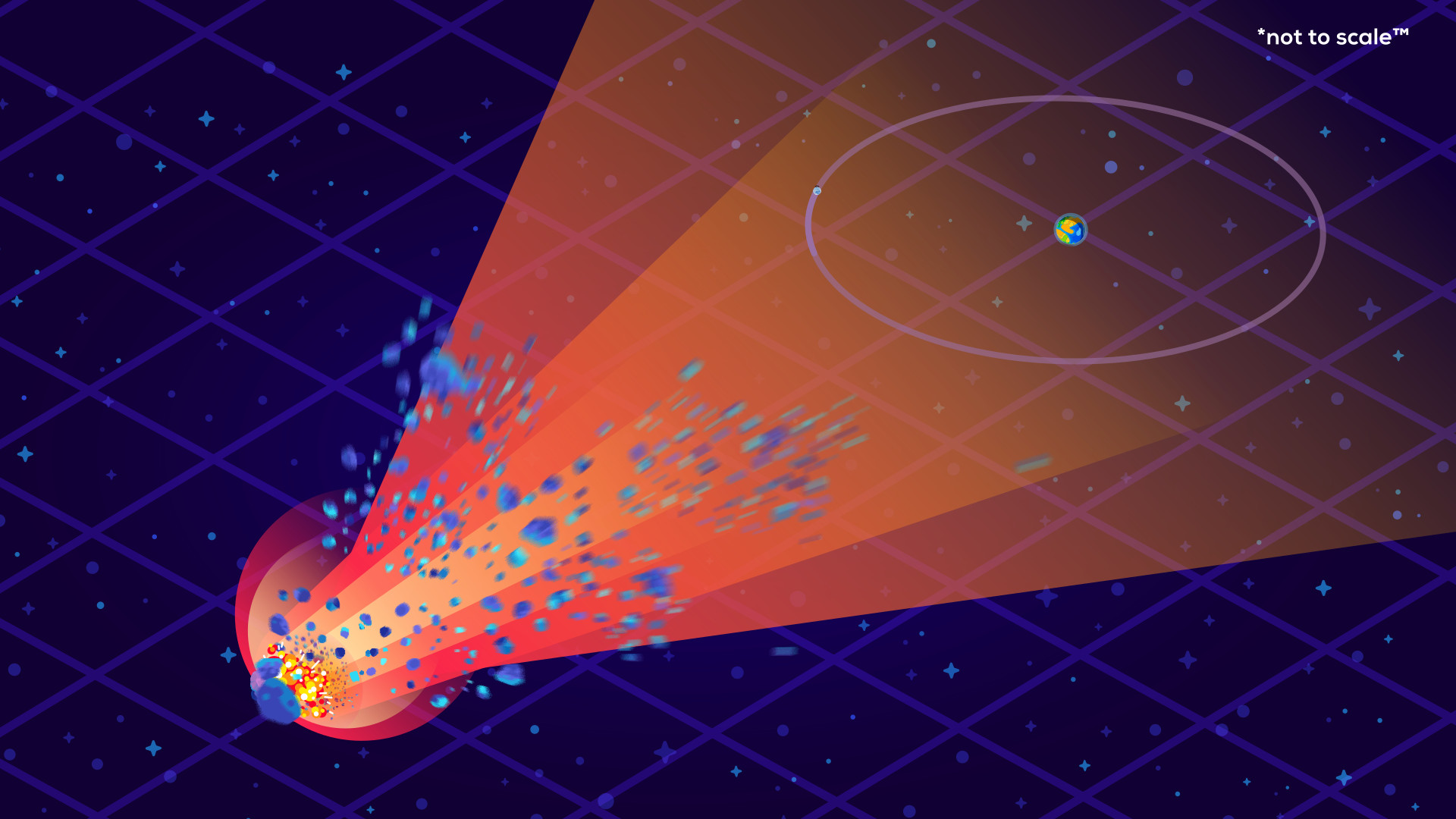

"Can Humanity Stop A Planet-Killing Asteroid?" The Kurzgesagt video featuring UCSB's planetary defense research has been viewed nearly 8 million times globally since its September 2024 release.

The story behind the story

The video’s viral success wasn’t just luck; it was the product of a meticulous, year-long collaboration to ensure scientific accuracy.

“This was not just a casual project,” explained Cohen. “It was a great honor to have them reach out, and it was clear from the start that they really care about getting the material right and working with the experts.”

The UCSB group, whose research includes the PI: Multi-modal Planetary Defense project (PI stands for “Pulverize It,” referring to the disruption of asteroid material), entered a rigorous back-and-forth process with the Kurzgesagt animators and writers. The challenge: How to accurately depict the physics of hypervelocity impacts — objects flying at speeds hard to imagine in everyday life — in a way that is engaging and, well, correct.

The group’s research proposes a novel method for mitigating a “planet-killer” asteroid or comet. Instead of a single, massive impactor (like in the movies) or a nuclear standoff, the PI concept involves an array of small, rod-like “penetrators” that would “pulverize” the object, effectively turning a single, catastrophic bullet into a harmless cloud of dust.

“They were very receptive and open to suggestions and changes,” said Bailey, who was heavily involved in editing the script. “There was a really open communication back and forth, even with the time zone difference. To see a media corporation take scientific accuracy so seriously was great.”

A full-circle moment

For Bailey and Cohen, the project was more than just a line on a CV. It was, as the original pitch for this story noted, a “full-circle” moment.

“I had been watching their channel since I was 15 or 16,” Bailey recalled. “It’s hard to make concepts like black holes accessible, and they do it so well. It was a cool moment to go from being a fan in high school to being on Zoom calls with them as a scientific expert.”

That expertise was crucial. The team provided corrections, simulations and endless “very long emails” to help the animators visualize the un-visualizable. The result, Cohen noted, was a “spectacular reaction” from peers and the public.

“They did a really good job of rendering what would happen if this actually occurred, based on our simulations,” Cohen said. “It also started a great conversation in the comments section. It’s great to see people are so interested.”

Science communication for a new generation

For Professor Lubin, who has worked on NASA-funded outreach for decades, the collaboration was a meaningful lesson in modern science communication.

“Most of our efforts go into scientific inquiry, but we also have tasks from NASA for outreach — to translate our work into a way the general public can relate to,” Lubin said.

The public, he noted, is highly motivated by this topic, driven by movies and recent events like the 2013 Chelyabinsk meteor.

“This was a nice story because it presents a threat but also a solution,” Lubin said. “It presented a challenge to humanity in a humorous, accessible way.” It’s a model of success for a university renowned for its physics program — a place where Nobel laureates’ work is foundational and where the next generation of researchers is already finding new ways to share that world-class science with millions.

Header illustration courtesy of Kurzgesagt