Content:

Why are some people able to master a new skill quickly while others require extra time or practice? That was the question posed by UC Santa Barbara's Scott Grafton and colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania and Johns Hopkins University.

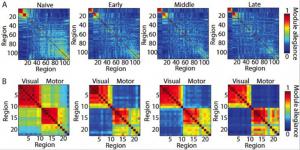

To find the answer, the team designed a study that enabled them to measure the connections between different brain regions while participants learned how to play a simple game. The researchers discovered that the neural activity in the quickest learners was different from that of the slowest.

The researchers' analysis provides new insight into what happens in the brain during the learning process and sheds light on the role of interactions between different regions. In addition, the findings, which appear online today in Nature Neuroscience, suggest that recruiting unnecessary parts of the brain for a given task -- similar to overthinking the problem -- plays a critical role in this important difference.

"It's useful to think of your brain as housing a very large toolkit," said Grafton, a professor in UCSB's Department of Psychological & Brain Sciences. "When you start to learn a challenging new skill, such as playing a musical instrument, your brain uses many different tools. With time and practice, fewer tools are needed and core motor areas are able to support most of the behavior. What our laboratory study shows is that beyond a certain amount of practice, some of these cognitive tools might actually be getting in the way of further learning." Such appears to be the case with slow learners.

At UCSB's Brain Imaging Center, study participants played a simple game while their brains were scanned with fMRI. The technique measures neural activity by tracking the flow of blood in the brain, highlighting which regions are involved in a given task. ![]() READ MORE (UCSB's The Current)

READ MORE (UCSB's The Current)